Distillation Cuts: How Distillers Decide When to Make Cuts

I decided to name my blog "The Heart Cut" because I've always been fascinated by the science and art of distillation. The hearts are the desired parts of the distillate a distiller wants to keep to age and eventually turn into whisky (or bottle and sell for clear spirits like vodka or gin). The hearts contrast with the heads and tails, two parts you don't want in the final product. This post will cover why cuts are necessary and how distillers determine when to make them.

Why Make Cuts at All?

When fermentation occurs, a host of chemicals are left in the mash, sometimes called "distiller's beer." This mash is then distilled to concentrate the alcohol. While flavorless on its own, alcohol is the mash's movie star, carrying an entourage of flavor compounds.

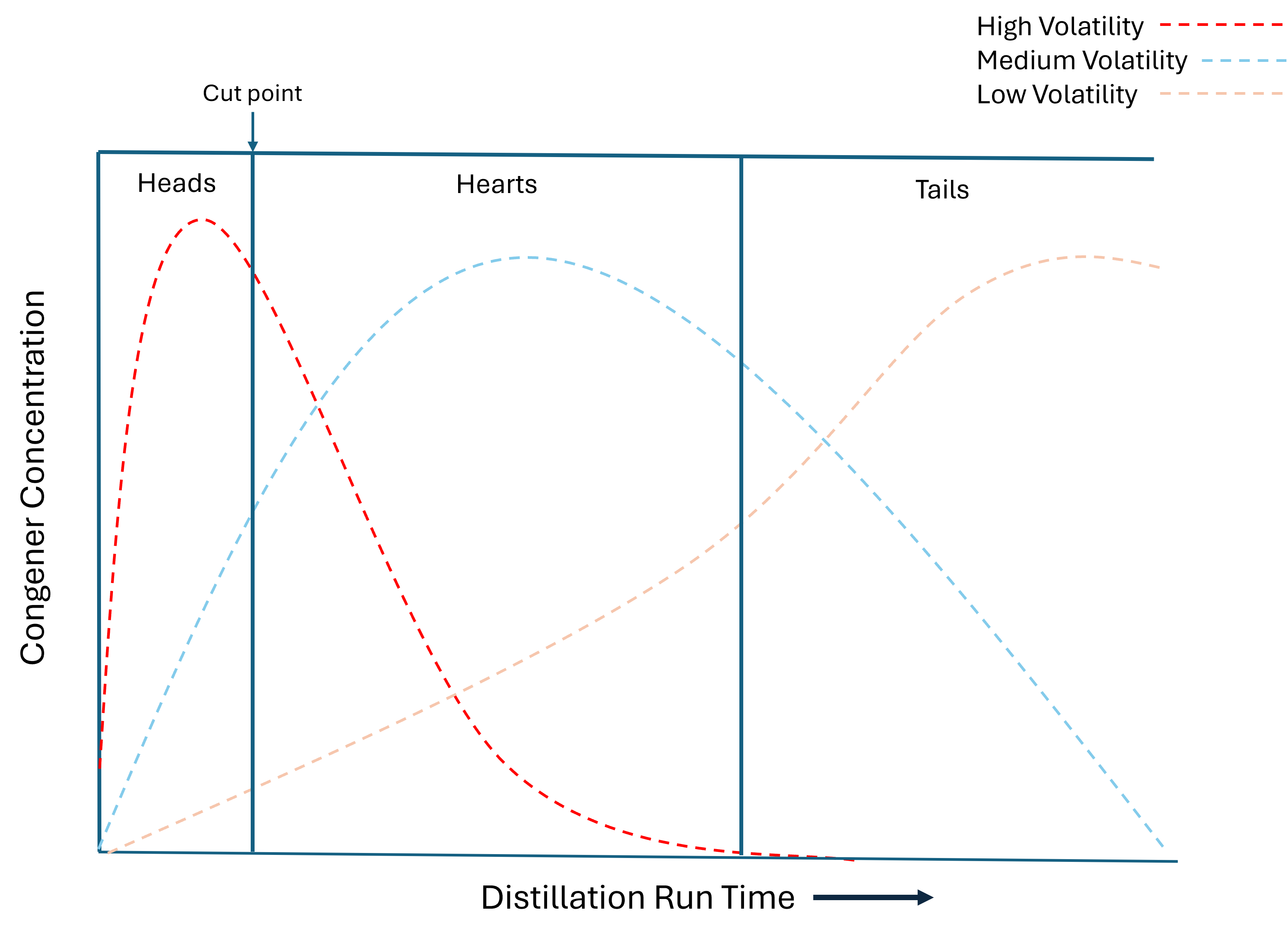

Every compound or chemical in the mash has a separate boiling point. More volatile compounds require less energy to vaporize; thus, they appear in the distillate first. Over time, less volatile compounds will increase. Distillers organize the distillate into various parts using cuts, sometimes called "fractions."

Cuts are necessary for two reasons. First, some of the highly volatile alcohols, methanol, in particular, are dangerous if consumed in large amounts. Second, the flavors change drastically throughout the distillation process, so distillers have to decide when to make cuts based on their desired flavor profile.

The first distillate off the still is called the heads or foreshots, where the most volatile and light compounds emerge, giving the new make an astringent, solvent-like quality. These compounds cannot enter the final product and are often collected and redistilled in the next run.

Over time, more ethanol and other favorable compounds ease into the distillate. These are kept and put into casks. The final collection of compounds, known as the tails or feints, are also collected to be redistilled the next time. Where a distiller decides to switch from the heads to hearts to tails decides much of the whisky's final character. How do they choose?

Sensory Analysis

The romantic ideal of using sensory analysis to make cuts permeates the minds of whiskey enthusiasts. We want to believe that the master craftsman decides when to make cuts by tasting the alcohol from the still. Is it really that simple?

Well, yes, it can be. I recently did just that at Andalusia Whiskey Company in Blanco, TX. You can clearly taste the difference between heads and hearts, with heads assaulting the senses with acetone and paint thinner until the hearts appear with a slightly sweet stream of ethanol.

However, depending solely on sensory analysis to make cuts is dangerous. Every person has a different palate, so depending on a master distiller's sensory analysis alone may lead to inconsistencies if they move on to another role, retire, or are unavailable. When someone else runs the distillation, they may choose different cut points. Also, even the same person's palate will change depending on the time of day or what they've eaten.

Also, there are some places where you can't legally taste the distillate. In Austria, for example, distillers cannot access the distillate as it comes off the still, and sensory analysis is impossible to use for cuts.

Sensory analysis has its place in making cuts, assuming it's legal. However, distillers shouldn't use it exclusively to decide cuts. It's best to use it with one or more of the following methods to ensure quality and consistency.

Factor #1: Time

Time can effectively measure when to cut because different congeners appear in varying concentrations throughout the distillation. The graph below shows an example of the concentration of various congeners over time.

As you can see, the high-volatility compounds burst then bust, while others spread more evenly. These shapes depend on how much energy you apply to the system. Running the still too hot will cause smearing, where these curves blend into each other, reducing cut-point precision. Have you ever felt an unpleasant physical reaction to nosing a whisky, like a gut punch to your olfactory bulb? This reaction indicates that the distillers may have cut from heads to hearts too soon, or the still was run too hot, and those high-volatility congeners made it into the hearts in greater concentrations.

Time is a common secondary factor often used in conjunction with others. For example, a master distiller may start up the still and set a timer for 30 minutes, knowing that at about 30-35 minutes, more desirable congeners start appearing in greater concentrations. At 30 minutes, they can begin sensory analysis to gauge the distillate. Every distillery discerns what is best for their desired profile. Some may run at lower temperatures, leading to heads that last for hours.

Factor #2: Volume

Distillers who use volume for cut points calculate each group of congeners based on the still's initial charge. For example, you can expect that the heads will amount to roughly 1-3% of the final distillate for any volume of low wines. Therefore, if you distill 1,000 liters of low wines, you'll expect 10-30 liters of heads. Depending on your desired profile, the hearts are pretty variable, taking up 15-80% of the final distillate.

Volume isn't as helpful because temperature affects it—temperature fluctuations in the water between winter and summer lead to different volume expectations for each congener group. Consistency is vital with whiskey, and volume alone isn't consistent enough.

Factor #3: Alcohol Concentration

Alcohol concentration is an excellent factor in deciding cut points thanks to its ease of measurement and consistent results, assuming fermentation went according to specs.

Throughout a distillation run, the alcohol concentration starts small, spikes, and then reduces. The cut from heads to hearts typically occurs shortly after hitting the highest concentration. At some point, the distiller must decide when to cut to the tails. Sensory analysis helps zero in on that point.

A typical heart cut runs anywhere from 75% to 55% alcohol by volume (ABV), based on the desired profile. A peated whisky should be cut closer to 55% or lower because many smoky and peaty notes appear in the tails. Also, if the distiller plans to age for a long time, they can cut deeper into the tails. If they want a younger whisky or to use second- or third-fill casks, they'll want to cut higher, closer to 65% ABV.

Factor #4: Temperature

Temperature is a factor that is more useful for neutral spirits than for whiskey, but whiskey distillers still benefit from checking temperature readings throughout the process.

Typically, temperature probes are inserted at different points in the still, Lyne arm, and condenser (and plates if using a column or hybrid still). Since different compounds have different boiling points, distillers can roughly determine what might be coming out of the still and in what concentrations based on the temperature. This factor is best used in combination with others.

Tools in the Toolbox

These four factors have differing levels of effectiveness, but all are tools distillers can use to decide when to cut. With enough experience, distillers can create guidelines that lead to consistent results with every distillation run. Fermentation creates flavors, and making cuts decides which flavors make it into the barrel and ultimately into the final whisky.